Passion builds Poetry

For the first time in my life I get an insight view of the poetry of skateboarding. Skating means to make impossible dreams possible, that's what Jack from Uganda told me. He is now 40 years old and can still remember when he saw the first skateboard of his life. How he tried desperately to make friends with the owner. How he built the first skate park in Uganda and that the authorities had no idea what he was up to. How he shared his first skateboard with others until he could hardly ride it himself. How skateboarding made him dream again. He grew up in the ghetto and didn’t know no dreams and perspectives. However, his passion for skating has opened many doors for him and since then he has been able to visit several projects worldwide. He likes to talk about an encounter with another skater at his first own half pipe. The visitor came very late in the evening and so they set up lots of candles around the pipe so that they could still skate all night.

As we drive through the city by car, I listen to the skaters' conversations. How they rate this and that place and where they like to go. How much they love the sound of the wheels when it changes on different surfaces. That they sometimes forget everything around them and just absorb this sound.

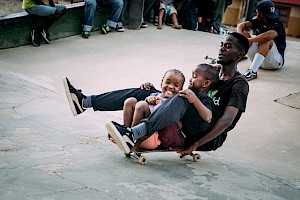

Learning means falling down and getting up again…that seems to me to be the mantra of skateboarding and you learn that falling is not the end of the world. You just fall and get up again. In a skate park you’re a big family, there are no “gangs”. No matter if you are shy or loud, skateboarding unites and everyone can find real friends in this way. Tobi tells me from South Africa that the skate park there is the only safe place for the street kids, where they don't have to be careful all the time so that nobody steals their shoes or their food.

Skateboarding is also about making your own decisions. Unlike many other things in life, skating means freedom and independence. At school we are forced to learn something. We often have to comply with our job. But on a skateboard we decide what we do. JUST DO IT. The permanent tension promotes concentration and like most sports it clears the mind. The passion for skating has changed the whole crew in different ways. The experience of getting up again after falling down is an important experience that increases self-confidence and strength to get a better grip on their other problems in life.

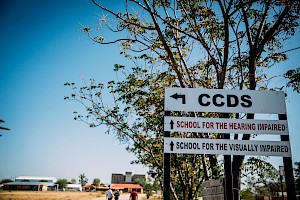

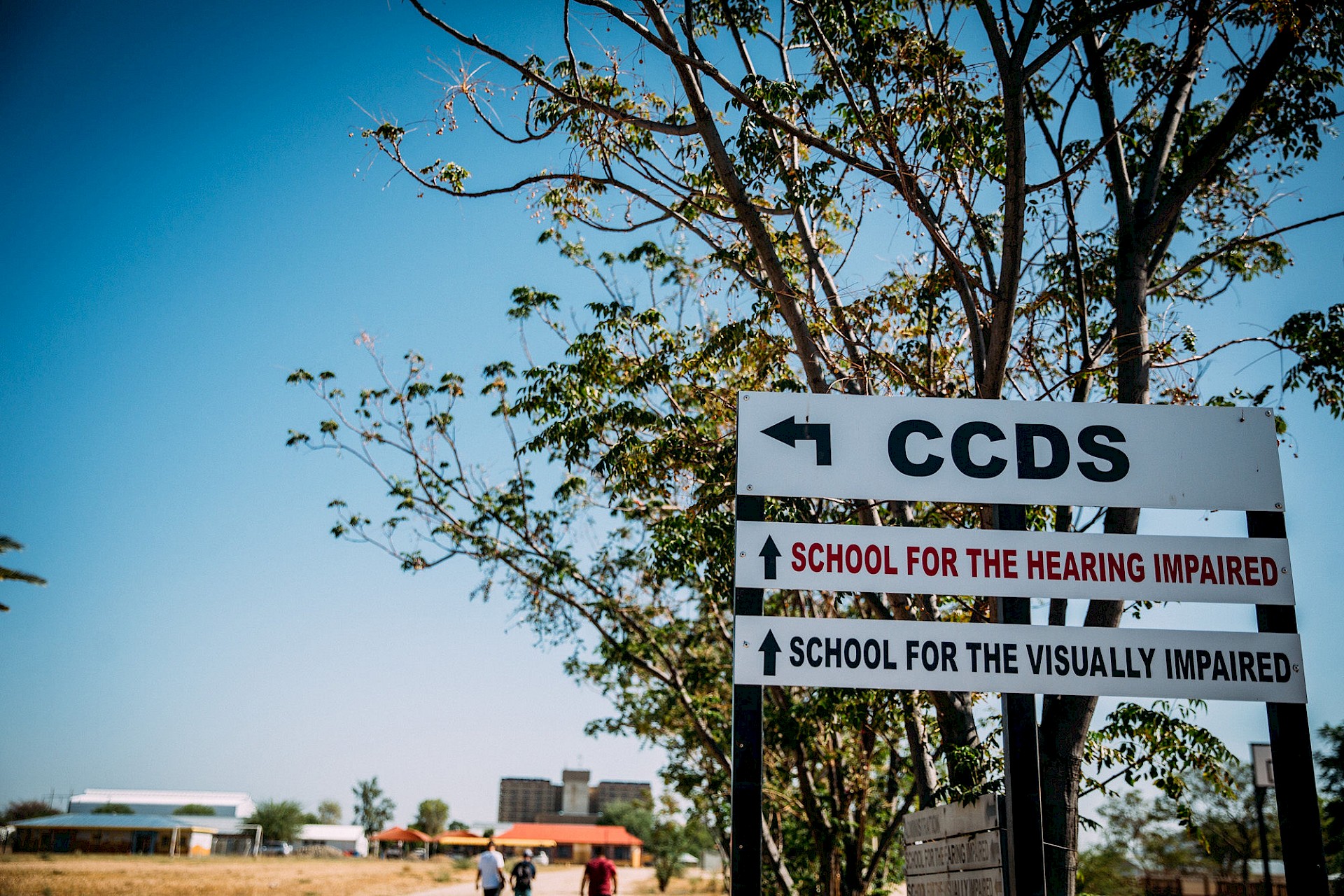

In conversation with the teachers of the school, I am surprised how positively they speak about skating. How the kids rave about it and have learned to overcome their fears. How brave some of them have become and how their character has strengthened. That the kids don't just get up after a fall, but also stand up for their opinion. The school teachers also motivate their children not to give up and keep practicing. It’s an important life experience to risk something. This is practiced every day in the skate park. It's no exaggeration to say that the skateboarding community is peace-building. It brings people from different countries and social classes together and lives by its open-mindedness.

But I also learn about the high youth unemployment rate here in Namibia, which is around 50%, and that wages are rarely enough to live on. Therefore, the crime rate is pretty high too and very difficult to deal with. Persistent corruption and latent racism make social interaction even more difficult.

For the next day I plan a tour through various slums. Maria, a political activist, invites me to her friends and explains why it is so difficult to get out of poverty: the unemployment rate is high and women rarely work anyway.

At 10 a.m. on Saturday morning we sit together between some drunk residents of the Katatura Township in a corrugated iron hut pub. For me personally, such encounters are the most interesting ones on my trips for aid organizations. We chat, among other things, about the beer-like brew of millet and sugar that most of the people drink, who don't have money for beer. Alcoholism is a big problem here in Namibia. Two men sit in front of me and ask me a lot of questions about Germany while I ask them how you can have 10 children of different women without taking care of them or supporting them financially. Maria asks the two of them if they’re not afraid of HIV. One of the two says no, because he already has it.

At home, I would probably not ask someone I just met in a pub why he didn't use a condom. But when I'm traveling I am often very direct and I notice that no matter how private my questions are, people are happy when someone listens to them and that you are interested in them. For me personally, it’s always valuable to change the point of view and to find out reasons.

There’s illegal electricity in some of the corrugated iron huts, but none of them has water. There is a chip card for everyone with which you can buy 25 liters of water at a tap for 100 Namibian dollars (6 euros). If the credit on the card is empty, the family can no longer draw water.

The vicious circle of poverty is very similar to that of other countries. No money for education, teenagers become parents, a high unemployment rate and an upper class that supposedly doesn't want to give up their privileges. Lack of water will most likely be a major problem in the future. Here in Windhoek, the river is almost completely dry. I find a little water at the reservoir, which is completely contaminated by toxins. Kai from the school project tells me that crocodiles from dry pools are already moving over the mountains to find some water.

You don't feel any of these problems at the skate park. He is unaffected by the difficulties of this country. You can hear the different sounds of the wheels on the surface and I photograph the silhouettes of the skaters in the sunset. It seems like a safe retreat, where it’s about connecting to the board and clearing your head.

On the last evening there’s still skating until the moon rises. After the barbecue at the hostel, everyone celebrates together and a very nice last day comes to an end.

When the first group left this afternoon, the mood was chastened. Nobody really wants to go home. Numbers are exchanged and everyone said goodbye. I’m packing my camera bag and closing my laptop. In addition to many photos, I take all the beautiful encounters and small wisdoms home with me and again, the desire to support more good aid projects with my work. Because I also learned from staying here - Go with your dreams but go! - Just do it!

Text & Photos by Alea Horst

Alea Horst is a freelance photographer who’s voluntarily joining us on our trip to Namibia. And here she recorded her impressions for us.

imprint data protection Website powered by DREIKON in Münster